Prototype

Workers' dormitory room

Many of us would consider living in a densely cramped and poorly ventilated place intolerable, as the dormitories housing our numerous migrant workers often are. Although workers rarely complain openly about their living conditions, we should not assume that they are satisfied with their current living situation. A pre-Covid conversation with migrant workers by Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), an NGO that rallies for fair treatment of migrant workers, revealed a sombre feeling of resignation from the workers regarding their current living accommodations. Most do not voice their feedback to their employers, fearing they may lose their jobs if their bosses were offended.

Despite TWC2’s warning that overcrowding could lead to a rapid spread of infection, the inertia in addressing and improving existing conditions for workers cost Singapore dearly as the pandemic rampaged through the dormitories, forming the largest Covid cluster in Singapore.

Migrant workers form a crucial part of Singapore's city ecosystem, across all sectors from construction and infrastructure to supply chains. How can we reconfigure migrant workers’ tight, utilitarian dormitories into liveable spaces with a sense of ownership and community? How can we let them feel that the rooms they rest in, while perhaps not home, are their spaces?

This was the question we considered together with a dormitory operator in light of the pandemic’s significant impact on the migrant worker community. In addition to examining the living conditions which exacerbated the pathogen’s spread, it was also critical to gain an intimate understanding of how workers used the spaces and their daily rituals, in order to find solutions that respected the workers’ autonomy, within practical operational limits.

The research was conducted in two phases. The first phase involved a site visit to an existing dormitory, to gain a deeper insight into their living conditions. Taking our observations to the drawing board, we prototyped a variety of preliminary layouts for the operator’s commentary. In the second phase, another round of layouts was designed, along with a participatory workshop, which aimed to give dormitory residents a platform to voice their thoughts, reservations, and suggestions, as well as for us to understand their habits, routines, and priorities.

This was the question we considered together with a dormitory operator in light of the pandemic’s significant impact on the migrant worker community. In addition to examining the living conditions which exacerbated the pathogen’s spread, it was also critical to gain an intimate understanding of how workers used the spaces and their daily rituals, in order to find solutions that respected the workers’ autonomy, within practical operational limits.

The research was conducted in two phases. The first phase involved a site visit to an existing dormitory, to gain a deeper insight into their living conditions. Taking our observations to the drawing board, we prototyped a variety of preliminary layouts for the operator’s commentary. In the second phase, another round of layouts was designed, along with a participatory workshop, which aimed to give dormitory residents a platform to voice their thoughts, reservations, and suggestions, as well as for us to understand their habits, routines, and priorities.

PHASE 1: SITE OBSERVATIONS & PROTOTYPING

During our first visit to the dormitory, some objects and their usages caught our eye. Observations are categorised by space and provisions:

| OBSERVATION | REMARKS |

| 1. Personal and Communal Storage | A storage pull-out cabinet is provided under each bunk bed for residents to store their belongings. However, most of them found it inconvenient for everyday items. Toiletries were also seen with food and drink items on the communal table. This results in an aggregation of personal and collective items scattered across the room. |

| 2. Privacy Issues | The room provides little to no privacy for bunk beds regarding lighting, sound, and visual barriers. |

| 3. Laundry | Due to the limited laundry space, residents find it easier to deposit their dirty laundry next to their beds. Residents also utilise bed frames as make-shift drying racks. This is concerning as indoor drying of wet clothing breeds mould, resulting in residents developing pneumonia. |

| 4. Electrical Appliances | Multiple fans were ‘illegally’ mounted and tied to bunk beds as there are no ceiling or wall fans in the room. Extension cords connecting the fans were dangling off beds and spreading across the floor. |

| 5. Cooking/Dining | Cooking equipment and food items were left beside the beds and floor. This may attract unwanted pests and rodents into the room. |

Following our observations and informal interactions on-site, layouts were revised to include these key provisions:

| NUMBER | PROVISION |

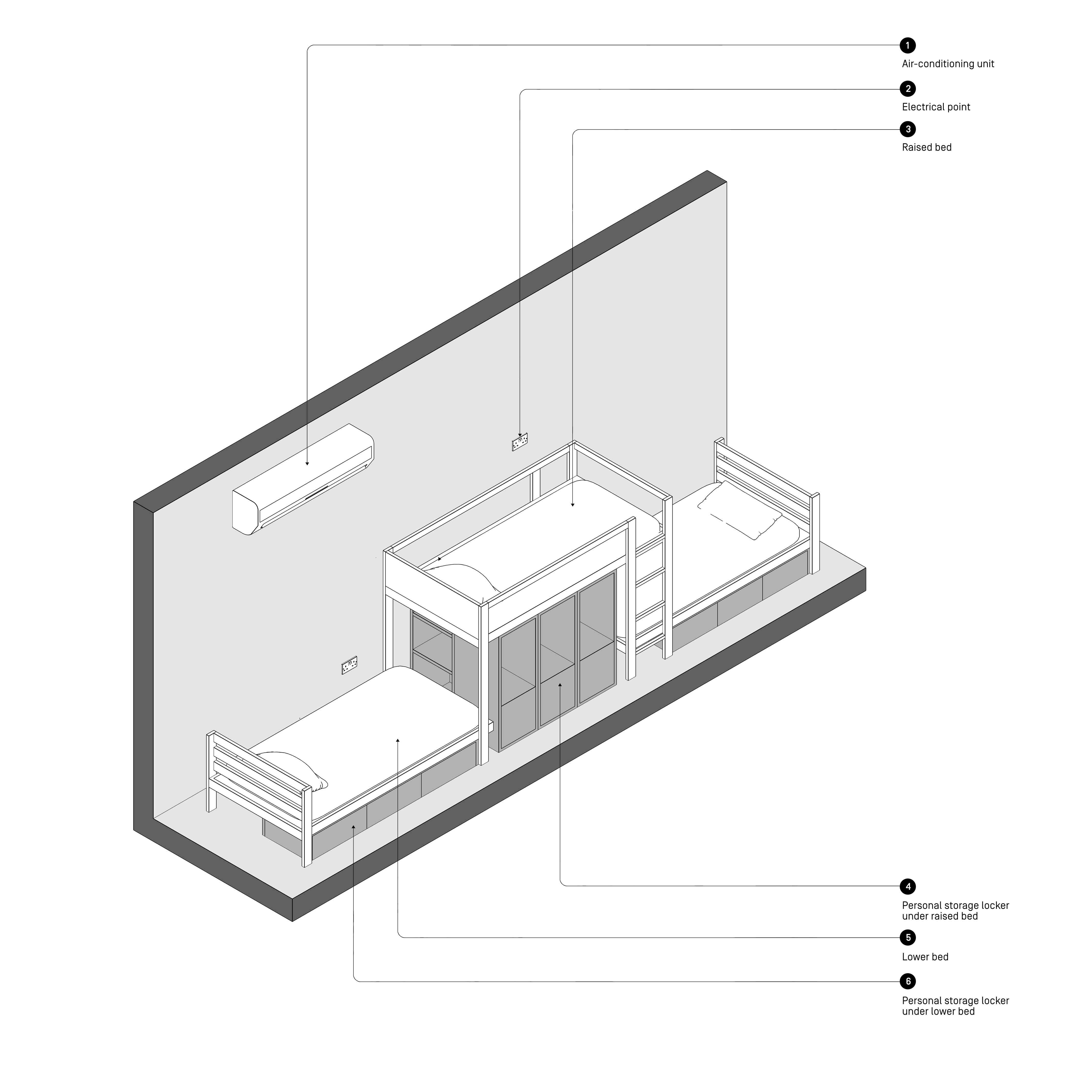

| 1. | Stacking beds to house personal storage lockers underneath, reducing spillage of personal items onto the floor. |

| 2. | Provide additional in-built appliances such as air-conditioning, wall fans, and sufficient electrical points for each occupant. |

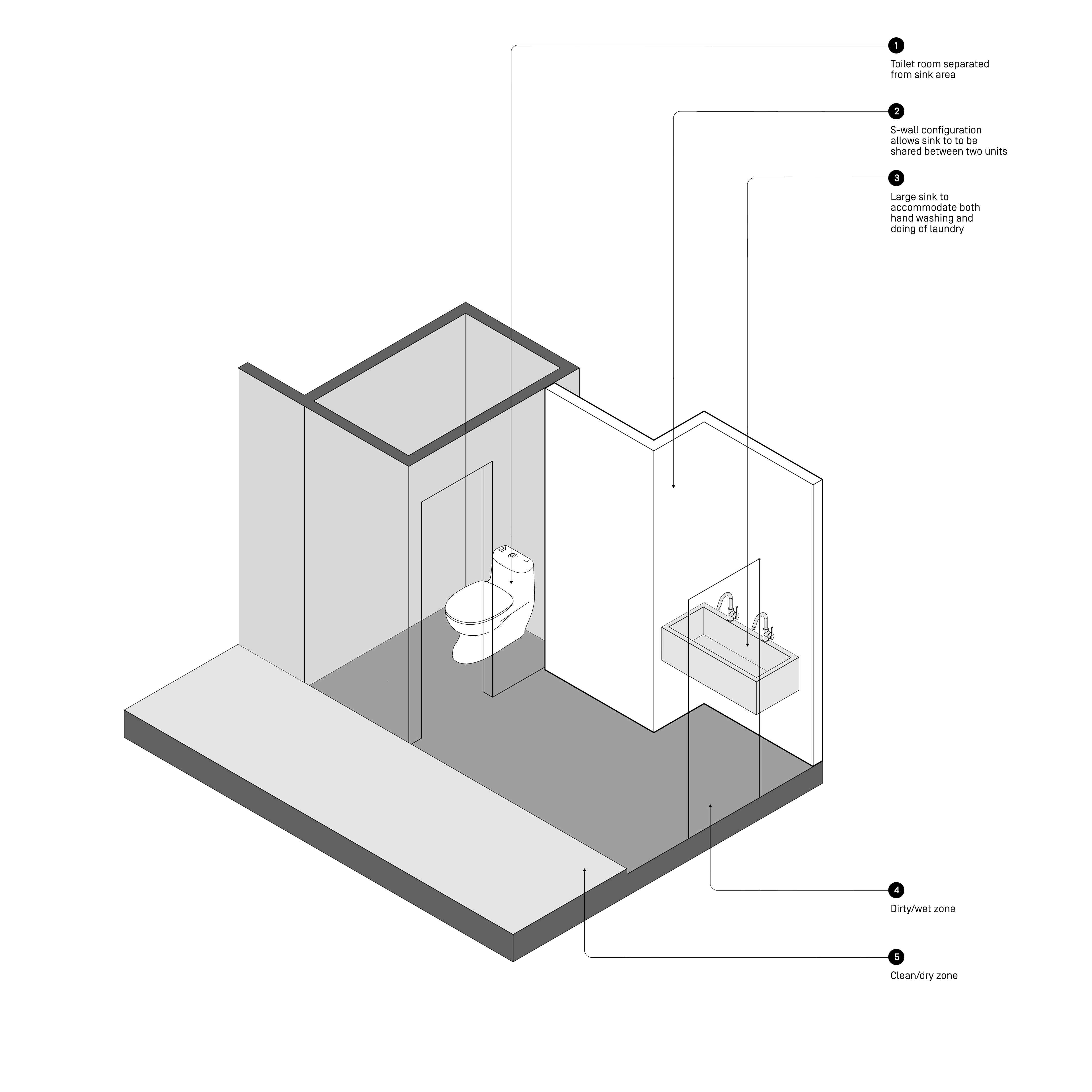

| 3. | Separating clean and dirty zones through changes in floor levels and finish. |

| 4. | Provide a separate sink from the WC that is large enough to accommodate hand washing and laundry. |

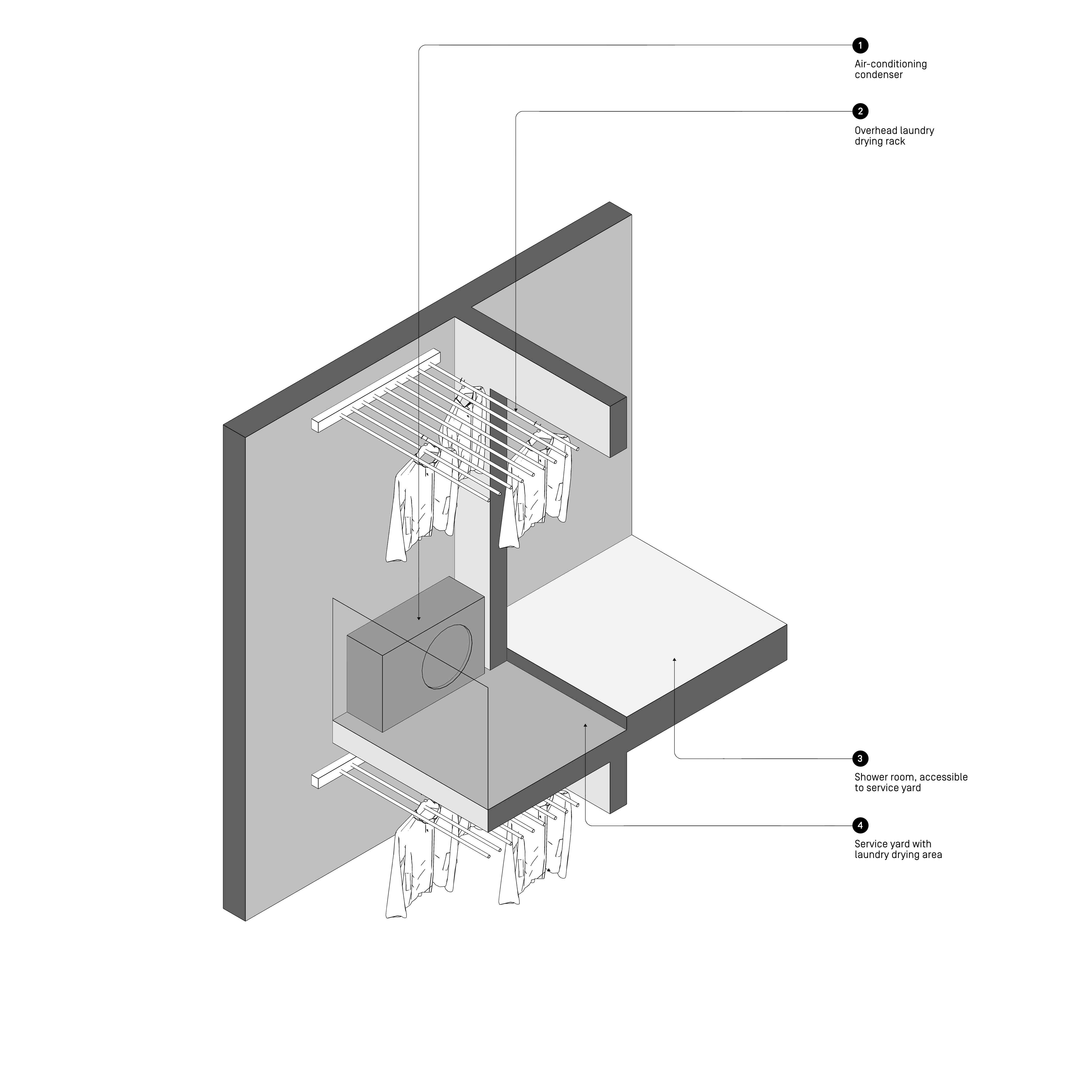

| 5. | Relocating the existing indoor drying area to the service yard, increasing space for wet laundry to dry. |

LIVING UNDER HOUSE RULES

The persistent subversion of rules and makeshift living observed required a deeper understanding of the workers' needs and living habits. Dialogues with both residents and operators highlighted an inherent conflict between their competing interests in a dormitory setting: the need to operate an efficient, clean and safe space for all, and the need for individuals to feel that their personhood--cultural habits, personal spaces, expressions of individuality--is respected. House rules intend to ensure that living spaces within the dormitory remain suitable for occupants to cohabit. Despite the operator's intention, implementation and enforcement are met with resistance on the ground due to conflict between the resident's way of life and how they should be living. The dormitory is also primarily regulated by the Ministry of Manpower, making it difficult to find a one-size-fits-all solution.

The persistent subversion of rules and makeshift living observed required a deeper understanding of the workers' needs and living habits. Dialogues with both residents and operators highlighted an inherent conflict between their competing interests in a dormitory setting: the need to operate an efficient, clean and safe space for all, and the need for individuals to feel that their personhood--cultural habits, personal spaces, expressions of individuality--is respected. House rules intend to ensure that living spaces within the dormitory remain suitable for occupants to cohabit. Despite the operator's intention, implementation and enforcement are met with resistance on the ground due to conflict between the resident's way of life and how they should be living. The dormitory is also primarily regulated by the Ministry of Manpower, making it difficult to find a one-size-fits-all solution.

PHASE 2: WORKSHOP WITH DORMITORY OPERATOR & RESIDENTS

The workshops carried out in the second phase aimed to gain a deeper understanding of how current conditions and restrictions impacted both parties, and what aspects and elements could be omitted, or should be prioritised. These findings are essential in thinking about the future design of dormitories.

Dialogues with the operators and residents branched into two areas:

1. What are some of the house rules that have been difficult to implement/follow, and why?

2. Are there any changes that should be made to the existing dormitory room design?

During the workshop with the operators, we learnt that the authorities hold them accountable for the cleanliness of the dormitories. Habits of littering out of windows need to be addressed, as they are often difficult to clear up and can cause safety issues down the line. The perception of the dormitory as a temporary living arrangement can be problematic, as the lack of ownership makes enforcement difficult. However, the operators also noted that dormitories regarded as being more 'premium' by the residents have a higher sense of ownership, cohesiveness, and cleanliness.

Five key iterations of the preliminary layout were developed from the provisions identified. Of the five prototype layout options shared with the operator, layouts 01, 03, and 04 were shortlisted for the workshop with the residents. The main priorities were:

Dialogues with the operators and residents branched into two areas:

1. What are some of the house rules that have been difficult to implement/follow, and why?

2. Are there any changes that should be made to the existing dormitory room design?

During the workshop with the operators, we learnt that the authorities hold them accountable for the cleanliness of the dormitories. Habits of littering out of windows need to be addressed, as they are often difficult to clear up and can cause safety issues down the line. The perception of the dormitory as a temporary living arrangement can be problematic, as the lack of ownership makes enforcement difficult. However, the operators also noted that dormitories regarded as being more 'premium' by the residents have a higher sense of ownership, cohesiveness, and cleanliness.

Five key iterations of the preliminary layout were developed from the provisions identified. Of the five prototype layout options shared with the operator, layouts 01, 03, and 04 were shortlisted for the workshop with the residents. The main priorities were:

| PRIORITY | REMARKS |

| 1. | Room configuration needs to be orderly, to comply with authority checks. |

| 2. | Provision of more storage space for residents, so their belongings can be appropriately kept away, allocated space for cleaning equipment, and shoe storage for work boots and non-work shoes. |

| 3. | Provision of outdoor air-drying racks for wet laundry. |

| 4. | Provision of one power point for each resident, to prevent overloading of extension plugs. |

| 5. | Provision of pantry area for hot drinks and dry food. However, eating in the room is highly discouraged due to pests. |

| 6. | Provision of desks for residents to use laptops. |

| 7. | Non-facing bed heads to reduce causes of conflict. |

| 8. | Individual bed-lights and screens for privacy. |

PROTOTYPE LAYOUT 01: SINGLE BEDS

A single bed layout occupies more floor area, limiting space for social activities. Residents can access personal storage from under beds and cabinets at the room's entrance. A door encloses the washing area to separate clean/dry and dirty/wet zones, and prevents the chilled air from leaking out.

PROTOTYPE LAYOUT 02: OVERLAPPING BEDS

Overlapping beds in this layout frees up more floor areas for social activities. Personal storage under the top and bottom beds further reduces the need to move between clean and dirty zones. Beds stacked against the window will however limit daylighting. The narrow space between beds may inconvenience access to storage cabinets.

PROTOTYPE LAYOUT 03: OVERLAPPING BEDS (PARALLEL CONFIGURATION)

Overlapping beds in this layout frees up more floor areas for social activities. There is a distinct separation between dirty/wet zones from clean/dry zones. Raised beds do not block natural lights coming in from the main windows.

PROTOTYPE LAYOUT 04: OVERLAPPING BEDS (SINGLE ROW CONFIGURATION)

Beds are aligned and stacked against one side of the room to free up more space at the end of the room for social activities. Residents go through the clean zone before entering the dirty/wet area to wash up. One of the beds directly faces the pantry.

PROTOTYPE LAYOUT 05: MIXED BED CONFIGURATION

A hybrid between Layout 02 and Layout 03, this layout follows the tightest bed configurations, while reducing the dirty zone to the entrance, opening up more floor areas for socialising in the pantry area.

WORKSHOP WITH RESIDENTS

A subsequent workshop was carried out with residents as a way to engage them, and provide space for them to voice their thoughts and concerns about their current living accommodations. The workshop format was designed to gather input on their existing routines, positions on house rules, preferred layout, and amenities required.

Residents were broken up into smaller groups of about 5, with 2 facilitators assigned to each group to explain the activities, facilitate discussions and prompt where necessary.

A subsequent workshop was carried out with residents as a way to engage them, and provide space for them to voice their thoughts and concerns about their current living accommodations. The workshop format was designed to gather input on their existing routines, positions on house rules, preferred layout, and amenities required.

Residents were broken up into smaller groups of about 5, with 2 facilitators assigned to each group to explain the activities, facilitate discussions and prompt where necessary.

ROUTINES

Residents were given cards with icons of different activities and asked to arrange them based on their daily routine in the dormitory. This was designed as a simple warmup exercise to break the ice between residents and facilitators. The routine map served as a prompt for facilitators to chat with the residents and learn how they utilise and interact with their surrounding spaces throughout their work and rest days. In general, all the residents had similar routines, with most differences in timing.

Residents were given cards with icons of different activities and asked to arrange them based on their daily routine in the dormitory. This was designed as a simple warmup exercise to break the ice between residents and facilitators. The routine map served as a prompt for facilitators to chat with the residents and learn how they utilise and interact with their surrounding spaces throughout their work and rest days. In general, all the residents had similar routines, with most differences in timing.

HOUSE RULES

For the next segment, we posed a similar question from our engagement with the operators: Which house rules do you find easy or difficult to follow? Each group was given a set of house rules (shown with iconography) and an activity board. They were asked to sort rules they found ‘Easy’ or “Difficult’ to follow as a collective. Subsequently, each group had a chance to present their boards to the larger group of participants.

This was an excellent opportunity to understand their resistance to specific rules and difficulties from their lived experience as a collective, versus individual opinions. While the majority found regularly cleaning and placing shoes outside of their rooms easy to follow, they struggle with the following:

| RULE | REMARKS |

| Using only approved electrical appliances | As there is only one ceiling fan in a room for 12, residents sleeping in the lower bunk cannot experience any airflow. Hence, they resort to installing their standing fan or ‘illegally’ mounting fans onto their bed frame. They also use unapproved electric kettles to make drinks and sometimes meals. |

| Cooking only allowed in the shared kitchen | This may not be practical, as an entire floor of residents shares only two kitchens. It would be difficult to schedule their cooking, especially within their limited hours after work. Different foods and dietary restrictions from different ethnicities can quickly become a point of contention. |

| No overloading of electrical sockets | There are simply insufficient power sockets in a room to be shared amongst twelve men. |

| Hanging laundry only in designated places | There is not enough space to hang their laundry in the wet areas. Residents resort to improvising, which often takes the form of indoor drying. Currently, two residents share one under-bed storage, which is insufficient. |

| Safe distancing measures | It is not realistic for residents to keep 1m from each other inside due to the limited size of rooms. |

| Others | The low water pressure in their bathrooms slows down the time residents need to shower. This creates an issue at popular times such as before work in the morning. Mattresses are also not provided by default. |

LAYOUT MOCKUPS

In the next section, we presented each group with 4 prototype layouts (Type A-D) derived from the workshop with the operator, rendered in floor plan and scale model showing the key furniture provisions. Residents would vote on which of the layouts they preferred, and explain why. They were then invited to shift the scale furniture around and indicate changes on the model to form a layout that they would best prefer.

TYPE A LAYOUT

TYPE B LAYOUT

TYPE C LAYOUT

TYPE D LAYOUT

The Type A layout was initially the most popular choice amongst the residents. The primary driver for their selection was the availability of kitchen space for cooking and eating, followed by not having to climb up onto a raised bed. However, after discussing with residents the pros and cons of having a clear threshold between their pantry area and the communal sleeping areas, they generally changed their decision to Type D with a suggestion to erect a wall to divide the sleeping and common area further. This separation allows residents to socialise in the kitchen without disturbing their roommates resting in bed.

Further concerns over Type D were collated and sorted into primary and secondary concerns:

Further concerns over Type D were collated and sorted into primary and secondary concerns:

| CONCERNS | REMARKS |

| PRIMARY: KITCHEN SPACE | A vast majority of the respondents favoured a kitchen within their unit compared to a communal kitchen. They highlighted those communal kitchens are usually overcrowded, as most residents cook simultaneously. Cultural differences across the entire dormitory may also lead to intolerance regarding cooking methods and ingredients in a shared communal kitchen. It would be easier to cook in a room than in a communal kitchen with strangers from other companies. Since some rooms already have self-initiated pot-lucks and cooking schedules, the intimate scale of the room kitchen also allows for peer bonding to occur within the dormitory unit. In addition, having a kitchen close to their bunks is convenient, especially after a night of shift work. |

| SECONDARY: BED ARRANGEMENT | Most residents shared that if the kitchens are not feasible within individual units, they will opt for Type A. They indicated that it would be more convenient to get into bed directly instead of climbing a ladder, especially when heading to work early or returning late, thus risking shaking the entire frame and disturbing their roommates. Residents also often make hours-long phone calls to their families, and having their own space on the bed gives them more privacy than the raised options. |

PREFERRED AMENITIES

Another important question asked was: how would you rank the items you would like to have in the dormitory room?

For this segment we presented an assortment of amenities in the form of playing cards to participating residents. Their task was to select and sort the cards into three categories: ‘must-have,’ ‘good to have’, or ‘no need.’ Residents were also asked to rank the top 3 items in each category.

| AMENITIES | REMARKS |

| MUST HAVE | Provisions for fans (for ventilation), linked kitchens, and power points were at the top of the ‘must-have’ list. Residents also highlighted that their current bed frames are unsuitable and hoped they would not be bought for the new dormitory as they often creak, disturbing their sleep. They would like to have a more robust bed frame that does not wobble when climbing onto the raised bed. |

| GOOD TO HAVE | Provisions for privacy panels/curtains, lockers, dining tables, air-conditioning, and a clothes rack for drying were under the ‘good to have’ items category. Residents highlighted that they currently have an insufficient storage area for both work and personal belongings. They require three different zones to separate clean clothes, sweaty clothes (for air-dry), and areas for personal belongings. In addition, small storage spaces for cooking utensils would be ideal as they are afraid their utensils might go missing in the communal kitchen. |

| NO NEED | Residents indicated that they do not need lamps, televisions, or desk chairs in their dormitory. Most residents use their mobile devices as the primary form of digital entertainment. Furthermore, they mentioned that the provision of television would cause conflict over who gets control of the channel. |

Our initial site visit to the dormitory revealed multiple concerns such as safety, hygiene, cleanliness, and personal space. There was no limit to the number of occupants and spacing requirements. Internal ventilation followed the Building and Construction Authority (BCA) requirement, which measures the area of the opening to an internal floor area without taking into account the number of occupants. The urgency to review existing standards was followed up by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM), Ministry of National Development (MND), and Ministry of Health (MOH). Authorities and stakeholders developed new guidelines for future dormitories to improve liveability and be resilient against pandemics, with SIA helming a study of dormitory architectural layouts.

With a robust framework in place, we seek to refine the development of living spaces for the workers' dormitories. We considered feedback from operators and residents to develop a nuanced understanding of their needs and how the future dormitory designs could accommodate the new guidelines with minimal conflict to the dormitory's day-to-day operation and workers' sense of home.

We hope this study has shed light on and addressed issues regarding the current living conditions of the workers' dormitory. Rather than seeing dormitories as a place to house workers, it is vital to consider their lived experiences within their current accommodation. Inviting stakeholders to be part of the design process enabled them to develop a mutual understanding and make meaningful compromises when planning for new dormitories.

BEST WHEN TAKEN WITH A PINCH OF SALT.

PLEASE EMAIL FARMACY@FARM.SG WITH YOUR FEEDBACK, OR IN CASE OF ANY INACCURACIES.

PLEASE EMAIL FARMACY@FARM.SG WITH YOUR FEEDBACK, OR IN CASE OF ANY INACCURACIES.

REF. NO.

PROTOTYPES-004-WORKERS-DORM

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

JAXE PAN, SRISARAVANAN SUBRAMANIAM, TAN QIAN ROU, AARON LIM

PUBLISHED