Prototype

From Soundscapes to Atmospheres

Operating as repositories of knowledge and information, museums are vital institutions that facilitate the research and contextualisation of tangible and intangible cultural artefacts and materials, and provide a framework for communication and education. The general public is a key target audience for such institutions; through exhibitions, the public encounters tailored and accessible platforms to learn, analyse, question, and contribute towards.

These curatorial environments are shaped through a vocabulary of spatial parts and elements, the fundamentals of which have remained largely unchanged. Walls and showcases compartmentalise and frame spaces, providing the backdrop to express curatorial narratives through a considered arrangement of artefacts. Additional elements and concerns — such as text panels, contextual design elements, lighting, and conservation controls — create hierarchies of presentation that guide audiences’ attention within a museum environment.

These curatorial environments are shaped through a vocabulary of spatial parts and elements, the fundamentals of which have remained largely unchanged. Walls and showcases compartmentalise and frame spaces, providing the backdrop to express curatorial narratives through a considered arrangement of artefacts. Additional elements and concerns — such as text panels, contextual design elements, lighting, and conservation controls — create hierarchies of presentation that guide audiences’ attention within a museum environment.

As the mandate of today’s institutions shifts towards enabling equitable access and ownership of collective cultural knowledge, a broader rethink towards conventional presentation methods is critical. Tasked with the twofold challenge of “mediating”1 between educating and entertaining a broad spectrum of audiences with limited patience for prolonged engagement2, and intense competition from other experiential and leisure experiences available3, exhibition spaces must concisely convey cultural knowledge, without sacrificing depth. “Memorability”, encompassing effective audience engagement and enjoyment, becomes a catch-all metric of measure for this. By shifting the paradigm from purely spatial to experiential, forward-looking exhibition designs play a vital role in enacting memorability.

FARM’s recent exhibition designs attempt to heighten memorability by layering sensorial and experiential strategies with spatial designs that are inventive and contextually-driven — we term this synthesised experience as “atmospheres”. Through the following two case studies, we explore how we have employed soundscapes and tactile experiences as pivotal strategies in creating sensorial and visceral atmospheres that are subliminally-stirring, and provide a framework for curatorial content to be subtly conveyed4.

FARM’s recent exhibition designs attempt to heighten memorability by layering sensorial and experiential strategies with spatial designs that are inventive and contextually-driven — we term this synthesised experience as “atmospheres”. Through the following two case studies, we explore how we have employed soundscapes and tactile experiences as pivotal strategies in creating sensorial and visceral atmospheres that are subliminally-stirring, and provide a framework for curatorial content to be subtly conveyed4.

Case Study 1 - Dislocations

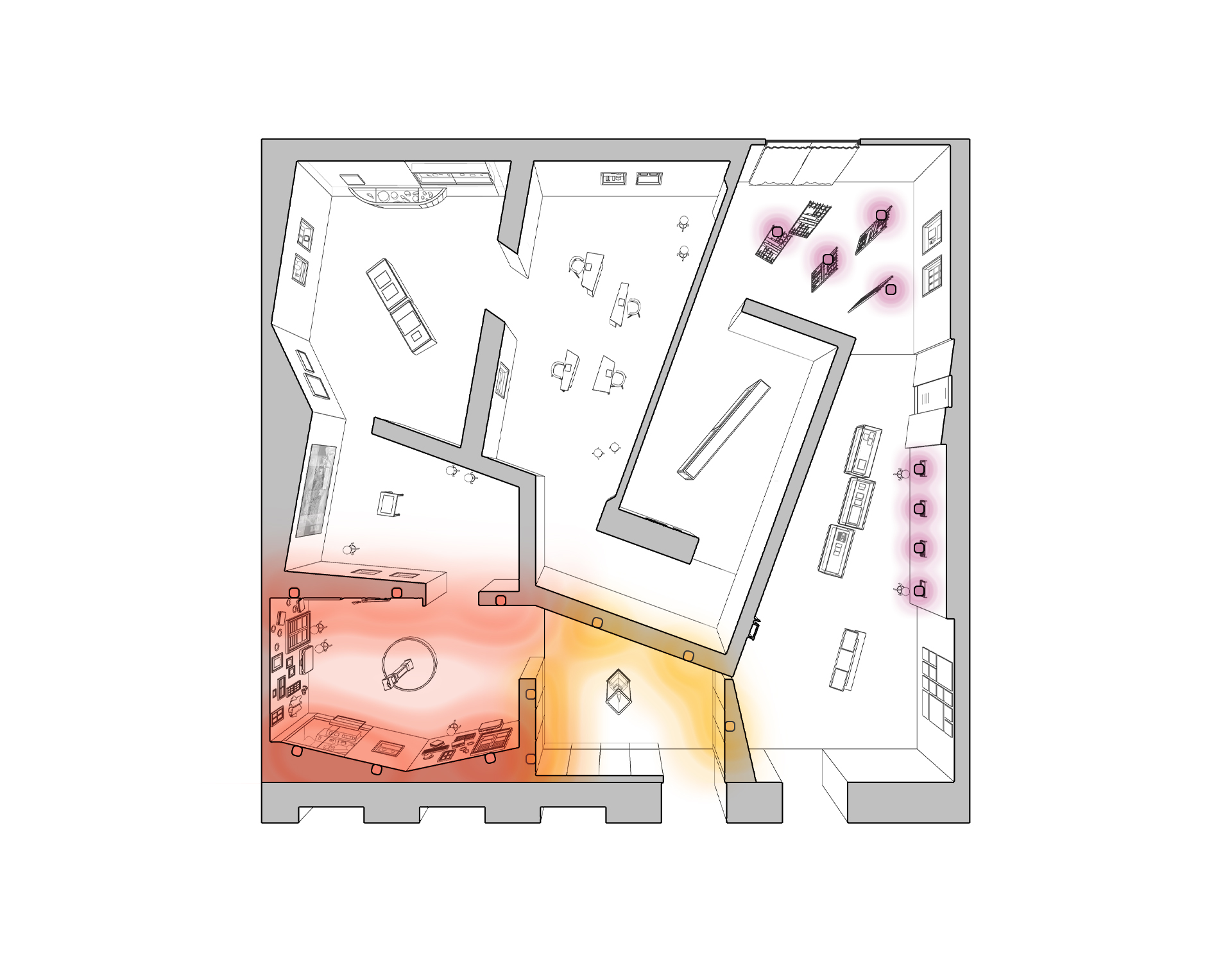

Reflecting the upheavals and disruptions experienced by everyday lives during the Japanese Occupation, the atmosphere within Dislocations: Memory & Meaning of the Fall of Singapore, 1942 (2022) is sombre, reflective, and intentionally disorientating at pivotal moments within the visitor journey. This atmosphere plays out within a series of interconnected polygonal spaces5 that are made expressive through the use of contextually-relevant materials and textures and calibrated lighting, to physicalise the sense of fragmentation and disorder implied by the word “Dislocations”. Additional layers of emotive soundscapes, large-format moving imagery, and reflective surfaces imbue the otherwise static space and artefacts with emotional resonance and depth. This is especially evident in the exhibition’s first two rooms — designed as immersive multimedia-driven atmospheres — that establish the curatorial and emotive angle of the rest of the exhibition.

The first room — irregularly-shaped, sparse and dimly-lit — immerses audiences into the exhibition’s curatorial narrative, and directs the attention of audiences through a controlled palette of spatial and sensorial elements. In place of a contextually-driven introduction, audiences are jolted from the museum’s sunlit atrium into an anachronistic fugue; an austere soundscape of voices recounting wartime stories in a variety of languages and registers looms overhead, complimented by fragmentary prints of quotes on the space’s carpeted floor, that are highlighted by spotlights fading in and out over them. This dissociative suspension of the present is further heightened as visitors catch glimpses of themselves seemingly entrapped within the dark-tinted mirrors lining the space, as they circulate about the singular totemic showcase displaying a chronometer frozen in time.

The second room continues and expands the emotive and sensorial ambitions of the first; the mirrors of the first give way to large-format multi-channel projections that cast an ambient glow over the space and all those within it. Audiences are transposed into the emotional context of 1942’s pre-war evacuations through a montage of archival footage and abstract moving imagery projected onto the highly-tactile surfaces around them. The space’s walls are lined with white-washed props that evoke the hasty evacuations of the time. This atmospheric composition is further articulated through the ambient audio track of complementary soundmarks playing overhead.

Spatial and technical limitations meant that the first 2 spaces had to be considered as an enmeshed atmosphere, particularly the aural experience, despite each section conveying chronologically-distinct fragments from a curatorial and spatial point of view. Eschewing directional speakers (which technically allowed for a higher degree of aural separation), non-directional speakers were installed and angled towards their respective sections to maximise the audibility and clarity of audio content. The resultant soundscape, blending oral histories from the first section and the soundmarks of evacuations and war from the second, attains a haunting quality throughout the first and second spaces. Serendipitously, this enmeshed aural atmosphere complemented the unintentional visibility across sections brought about through the mirrored walls of the first.

Cast Study 2 - Picturing the Pandemic

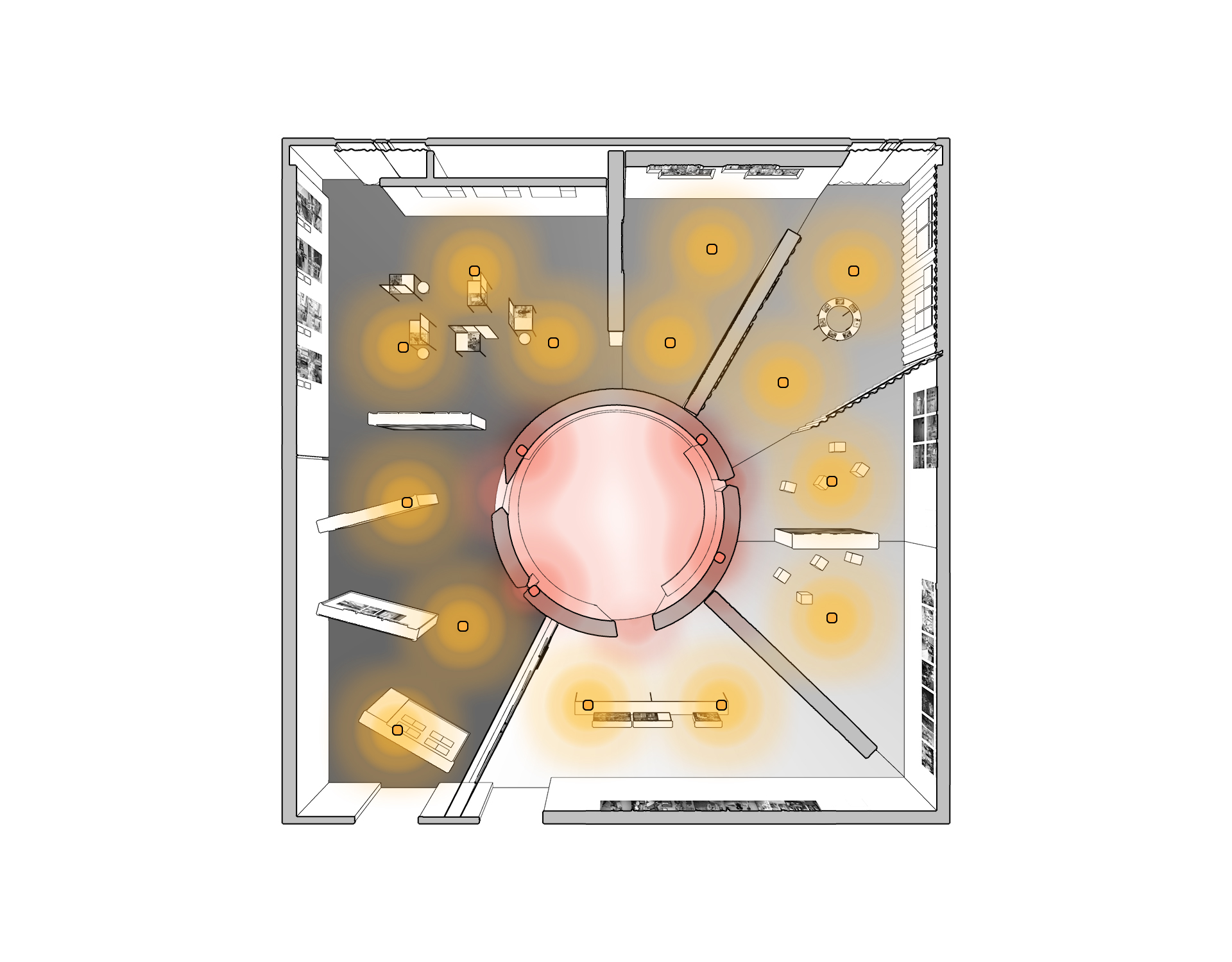

In contrast to the first case study, Picturing the Pandemic (2021) features a continuous atmosphere that is encountered across the entire exhibition. Circulating in a pinwheel fashion around a central rotunda and scattered abstract forms, audiences encounter over 300 commissioned photographs that thematically shift from an initial sense of uncertainty towards cautious optimism during and after Singapore’s 3-month long Circuit Breaker. This tonal shift is abstracted and expressed through a visual and tactile shift, from dark-toned materials to brighter and more expressive/textural ones, and culminates with audiences stepping into the white-stuccoed central rotunda, where a short film The Spaces Between Us plays.

An integral layer to this continuous atmosphere is a gallery-wide soundscape — a looping 13 minute-long ambient piece by The Analog Girl — that serves to modulate the emotional tone of the exhibition’s content. As audiences journey through the gallery, they experience a piece that expresses a sense of cautious optimism, that meanders through dissonance, pauses, and finds moments of resolution in leitmotifs. The emotional experience of audiences, shaped by how the photographs are paired with this soundscape, varies based on the moment they enter the space.

Playing on the relatability of the social-distancing requirements during the pandemic era, the exploration of proxemics and sense of scale became a key design strategy that shaped the broader ambience of the exhibition6. Photographs were primarily showcased through physical means, including an installation that abstracts empty hawker centre seats, monumental lightboxes, intimately-scaled apertures; certain photo collections were featured through novel projection techniques onto translucent surfaces.

A short film, The Spaces Between Us, plays within the exhibition’s central rotunda; it serves as a cumulation of, and underpins the exhibition’s content. Complementing the footage shown, soundmarks of life during the pandemic predominate the film’s audio track, ranging from birds chirping and classroom discussions muffled behind face masks, to the alarm-like sounds of hospital machinery and equipment. Due to inevitable sound spillage, this mix of soundmarks layers onto the exhibition’s broader ambient soundscape, lending a decidedly humanised touch, while also breaking its intended moments of calm at punctuated intervals.

Playing on the relatability of the social-distancing requirements during the pandemic era, the exploration of proxemics and sense of scale became a key design strategy that shaped the broader ambience of the exhibition6. Photographs were primarily showcased through physical means, including an installation that abstracts empty hawker centre seats, monumental lightboxes, intimately-scaled apertures; certain photo collections were featured through novel projection techniques onto translucent surfaces.

A short film, The Spaces Between Us, plays within the exhibition’s central rotunda; it serves as a cumulation of, and underpins the exhibition’s content. Complementing the footage shown, soundmarks of life during the pandemic predominate the film’s audio track, ranging from birds chirping and classroom discussions muffled behind face masks, to the alarm-like sounds of hospital machinery and equipment. Due to inevitable sound spillage, this mix of soundmarks layers onto the exhibition’s broader ambient soundscape, lending a decidedly humanised touch, while also breaking its intended moments of calm at punctuated intervals.

Postscript - Inclusivity of Senses

The two case studies present varied approaches at incorporating soundscapes within spatial settings to create evocative atmospheres — the first is intentionally fragmentary, while the second is a seamless experience throughout. Both seek to create immersiveness, and broadly argue at the relevance of such an approach at increasing memorability of curatorial content among museum audiences, and consequently enhancing a sense of collective ownership and engagement with it.

However, as we design for better inclusivity, we must recognise that the present palette of sensorial elements deployed — visual, tactile, and aural — might not be sufficient, particularly to persons with disabilities7. The collective cultural knowledge within museums and cultural institutions should not be off-limits to such groups because of inadequate design.

Taking cues from consumer and retail settings, perhaps the next frontier would be to design with olfaction in mind. The introduction of contextually-relevant scents into spaces can enrich atmospheres, so as to further “influence and shape people’s imagination”8. This approach is not without challenges — whether it is conservation control guidelines, spatial constraints, or the broad variance among audiences’ instinctual responses towards scents9. Nevertheless, its capacity to thrill and engage is proven; it also promises to provide an enhanced degree of accessibility for those unable to experience other sensorial elements within these curatorial atmospheres.

However, as we design for better inclusivity, we must recognise that the present palette of sensorial elements deployed — visual, tactile, and aural — might not be sufficient, particularly to persons with disabilities7. The collective cultural knowledge within museums and cultural institutions should not be off-limits to such groups because of inadequate design.

Taking cues from consumer and retail settings, perhaps the next frontier would be to design with olfaction in mind. The introduction of contextually-relevant scents into spaces can enrich atmospheres, so as to further “influence and shape people’s imagination”8. This approach is not without challenges — whether it is conservation control guidelines, spatial constraints, or the broad variance among audiences’ instinctual responses towards scents9. Nevertheless, its capacity to thrill and engage is proven; it also promises to provide an enhanced degree of accessibility for those unable to experience other sensorial elements within these curatorial atmospheres.

1 Usherwood, B., Wilson, K., & Bryson, J. (2005). Relevant repositories of public knowledge? Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 37(2), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000605055357

2 McClinton, D. (2019, April 17). Global attention span is narrowing and trends don't last as long, study reveals. The Guardian.

Retrieved March 28, 2023, from

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/apr/16/got-a-minute-global-attention-span-is-narrowing-study-reveals

3 Kelly, L. (2004). Evaluation, research and communities of Practice: Program Evaluation in museums. Archival Science, 4(1–2), 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-005-6990-x

4 Guzy, M. (May 4, 2017). The Sound of Life: What is a Soundscape? Folklife Magazine.

Retrieved March 28, 2023, from

https://folklife.si.edu/talkstory/the-sound-of-life-what-is-a-soundscape

5 Bertamini, M., Palumbo, L., Gheorghes, T. N., & Galatsidas, M. (2015). Do observers like curvature or do they dislike angularity? British Journal of Psychology, 107(1), 154–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12132

6 Chan, D. (2020). Combating a Crisis: The Psychology of Singapore’s Response to COVID-19. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

7 Wong, M. E., & Lim, L. (2021). Special Needs in Singapore: Trends and Issues. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

8 Hackett, P. M. W. (Ed.) (2016). Qualitative Research Methods in Consumer Psychology: Ethnography and Culture. Psychology Press.

9 Levent, N. & Pascual-Leone, A. (2014). Multisensory Museum: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

BEST WHEN TAKEN WITH A PINCH OF SALT.

PLEASE EMAIL FARMACY@FARM.SG WITH YOUR FEEDBACK, OR IN CASE OF ANY INACCURACIES.

PLEASE EMAIL FARMACY@FARM.SG WITH YOUR FEEDBACK, OR IN CASE OF ANY INACCURACIES.

REF. NO.

PROTOTYPES-006-SOUNDSCAPES

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

SEAN POON, TAN QIAN ROU

PUBLISHED

31.01.24